While countries routinely fret about supply chain resiliency, microchip manufacturing is uniquely vulnerable. It could hardly be more concentrated with Taiwan and South Korea producing over 80% of the global output. The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) alone is responsible for 55% of production, and much of that happens in its home base Taiwan which has long been a flash point for geopolitical tension between the U.S. and China.

While oil has been the most critical commodity powering the globe, microchips are becoming the linchpin of the emerging digital economy. To succeed in this brisk transformation, major economies need to build greater chip manufacturing reliance. This will entail improved organic capabilities and closer strategic relationships with global suppliers, but can America catch up? The history of the nation’s energy development reveals the answer will depend on government investment and business innovation.

Dash For Chip Independence

The capital investment and operating expertise to become world class in chip manufacturing is challenging. But developed economies are recognizing the need to onshore some production to prevent being held hostage to supply chain disruptions or geopolitical risk.

Japan, for instance, has put semiconductors at the center of its growth plans. It is looking to entice TSMC to set up a research facility and partner with local companies to advance chip making for use in 5G infrastructure, autonomous vehicles, and artificial intelligence.

Meanwhile TSMC is building a plant (its first in two decades) in the U.S. as it responds to Washington’s request and incentives to onshore some capacity. Intel is also gearing up its chip manufacturing capacity as both companies make substantial commitments to expand in Arizona.

All of this comes off the heels of a recent U.S. government report estimating that major supply disruptions in Taiwan could result in $500 billion of lost revenue for technology and electronics makers that depend on the island’s output.

Chip Volatility Resembles Oil

When governments scratch their heads and wonder how the world finds itself in this crunch, the answer is simple. The semiconductor industry is very volatile, which in the past drove many countries to outsource the headache.

It’s very expensive to develop onshore processing capacity. The expected price tag for each plant in Arizona, for example, is around $12-15 billion. They take up to two years to build and a decade to turn cash flow positive.

The other challenge is that semiconductor demand is erratic. The returns of the SOX Index, which captures the market value of the 30 largest global semiconductor related companies, have swung from down 50% in one year to up 75% over the next. That volatility is more than twice the overall equity market, and more in line with some of the wild swings in oil prices.

Semiconductor SOX Index Annual Returns

Source: Bloomberg, SLC Management

Semiconductors are notorious for boom and bust cycles, as breakthroughs can quickly disrupt existing demand patterns and force manufacturers to adjust. For a capital intensive businesses with high fixed costs, this can be very challenging.

Right now there are some seismic shifts in play: the uptick in handheld devices, data centers, electric vehicles, 5G infrastructure and artificial intelligence are all vying for chip output, and all these applications come with wide ranging demand estimates.

Government Action Needed

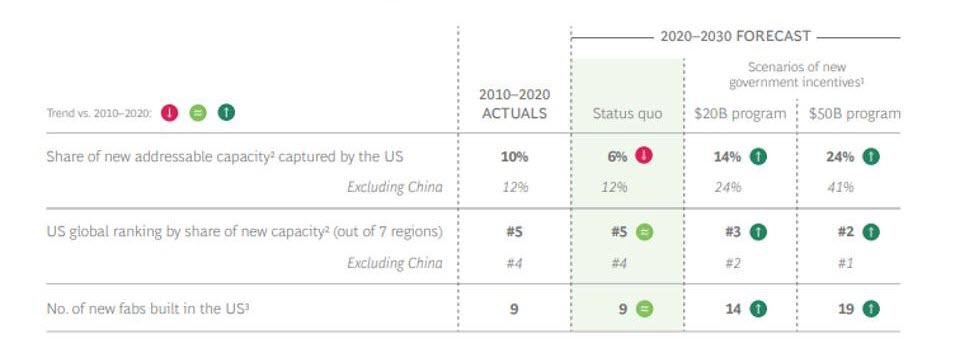

Dependable microchip production is quickly becoming a top economic and security concern for major economies. A joint study from the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA) and the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), expects chip demand to increase by 50% over the next decade. The report concludes that for the U.S. to regain relevance in chip making, government incentives are needed.

To have a shot at becoming a global leader and able to compete with China, SIA estimates that $50 billion of government funding is needed to revive the industry and arrest decades of U.S. chip making decline. The $50 billion has also received backing from a coalition of technology companies, and President Biden has penciled the request into his infrastructure bill. Therefore, some homegrown government and business partnerships seem like a natural solution given large upfront investment coupled with sophisticated business knowhow.

Exhibit – Potential Impact of New Government Incentives on US Semiconductor Manufacturing Position

Sources: VLSI Research; Semiconductor Equipment and Materials International (SEMI), second-quarter 2020 update; BCG analysis.

¹ Assumed to apply to new incremental capacity built in the US in the next ten years.

² Addressable capacity refers to the new capacity that the industry needs to add to serve the expected growth in demand, and that is not yet in development (remains available).

³ Normalized to an average fab seize of about 75,000 wafers per month (wpm) for comparison purposes, in line with the average fab size used in the 2020-2030 forecasts. The actual number of fabs built in the US in 20210-2020 was 19 (excluding experimental and very small units), with the average size of about 40,000 wpm.

Providing public funding for dependable chip making needs to be managed well, otherwise the favored national champions could limit competition and innovation. The defense industry is an example where a few key contractors dominate, making aggressive innovative and efficiency breakthroughs difficult.

However, America’s entrepreneurial instincts can be powerful with the right structure. As an example, the U.S. achieved energy independence on the back of technology breakthroughs in fracking that happened quicker than anyone imagined. The odds look good if it can succeed in a similar fashion with semiconductors, but it needs to move quickly with the right level of autonomy to allow business ingenuity. While the U.S. dominates the world in chip design, it needs to extend that to onshore manufacturing.

This article first appeared in Forbes. This material contains opinions of the author, but not necessarily those of Sun Life or its subsidiaries and/or affiliates.