With the news of the government eliminating RRBs from its funding schedule, we revisited some of our inflation replication research. Our research analyzed a wide range of strategies to replicate the Canadian Consumer Price Index, from using CPIs of other countries, to different commodity baskets, equity indexes and real estate. In the end, Occam’s razor seems to hold, with a partial exposure to U.S. CPI being a preferred alternative for replicating Canadian inflation. Therefore, we’re currently investigating potential benefits of a solution that tactically invests in both Canadian RRBs and hedged U.S. TIPS to provide a more liquid hedge for Canadian CPI.

Reflection: Were RRBs really in “low demand”?

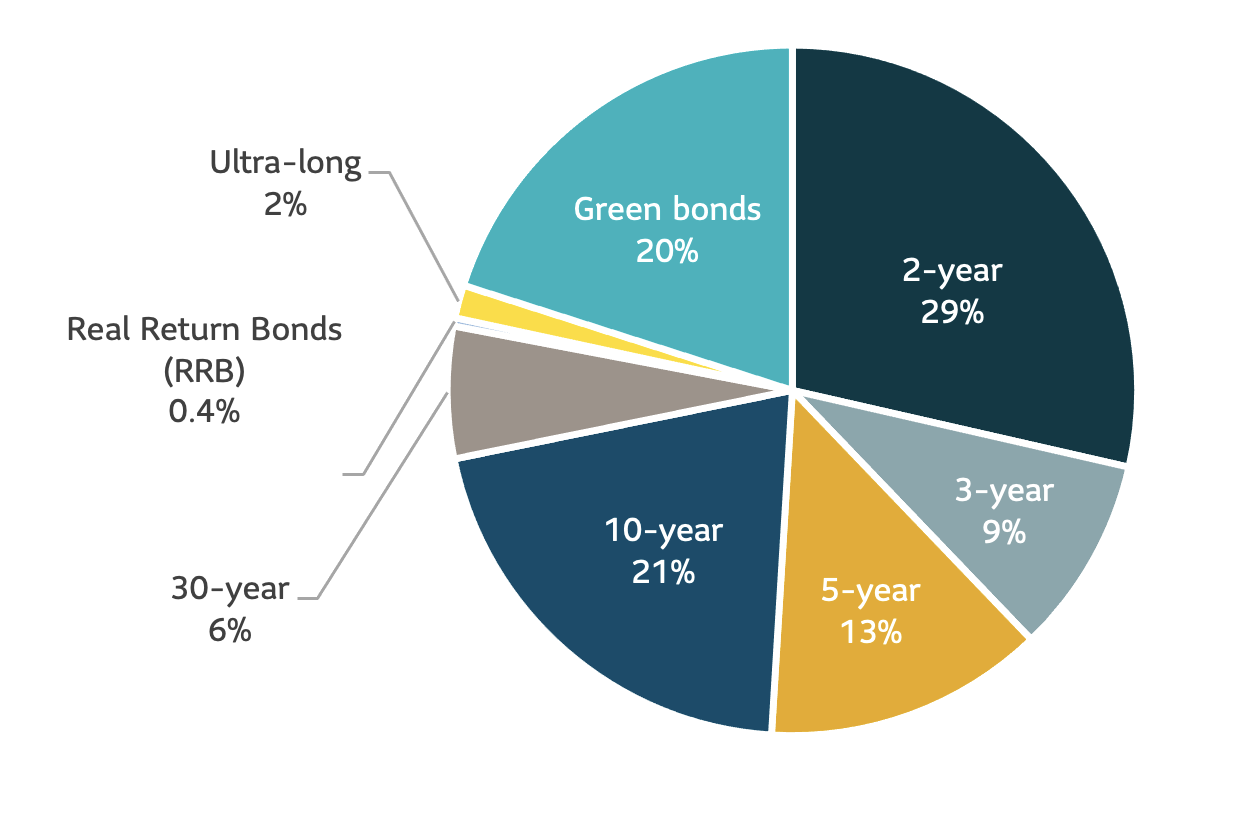

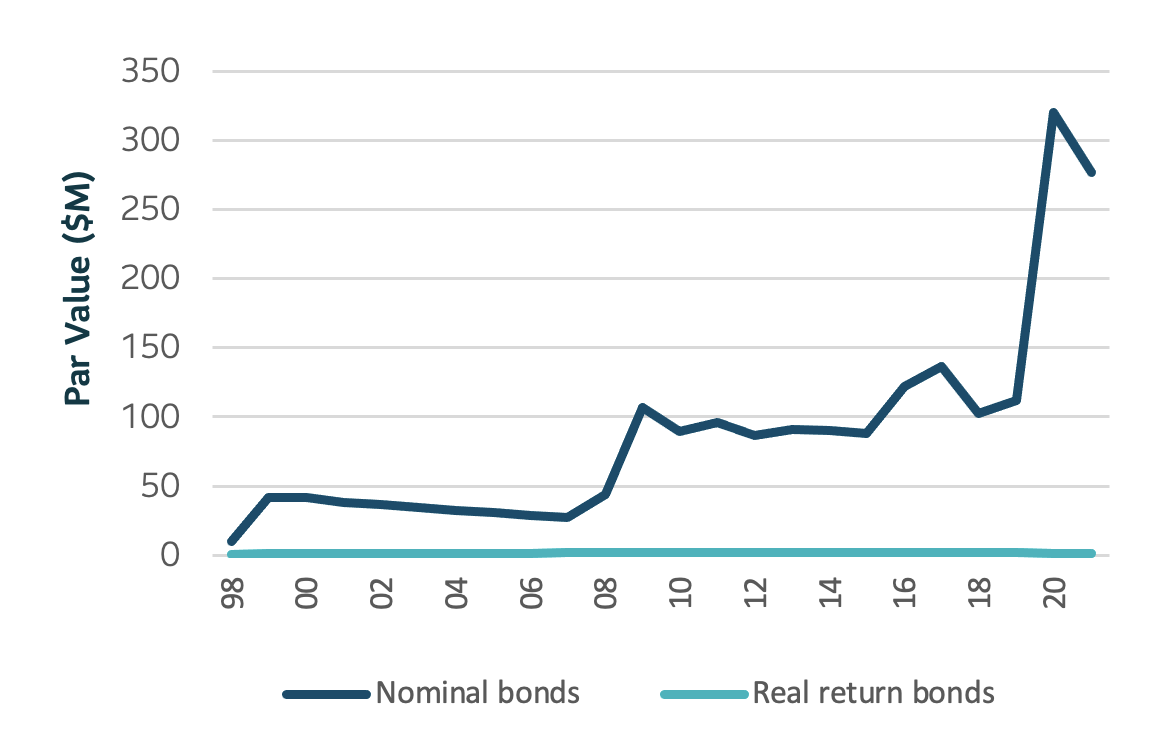

The Government of Canada cited “low demand” as a key consideration for the decision to cease issuance of RRBs. We investigated some key data points to help understand this consideration. Prior to the decision, RRBs as an asset class had the least issuance allocations in the fiscal 2022‒2023 budget (0.4%) among all other categories of bond issuance by the Government of Canada. While as a dollar amount, RRB issuance has remained relatively stable, nominal bond issuance has grown significantly over the last few years.

Budgeted Government of Canada bond issuances prior to announcement

Government of Canada bonds issued, by type

Sources: Government of Canada, Bank of Canada

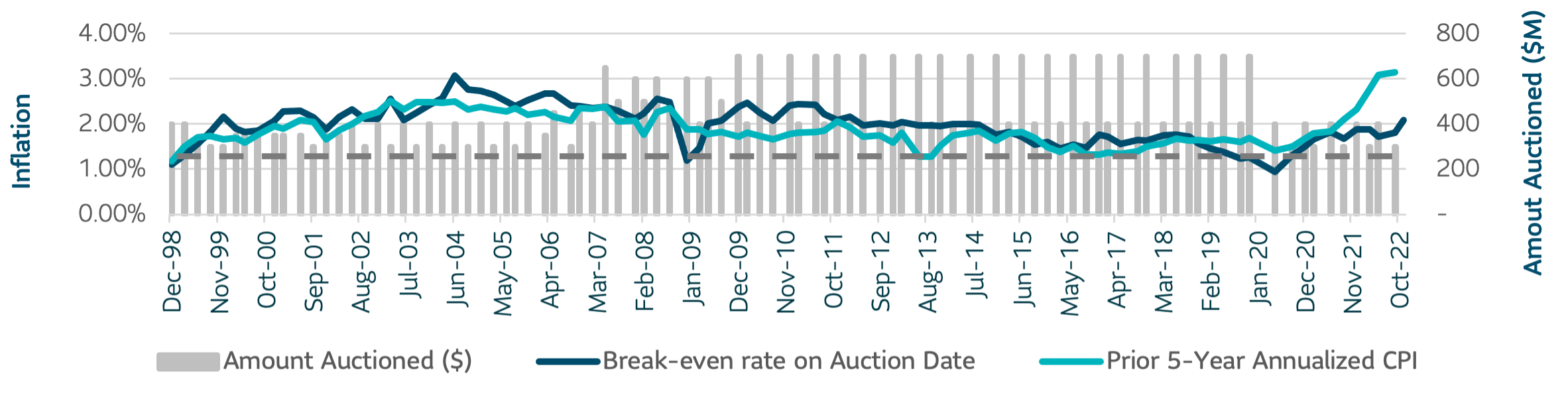

Given that most of the growth in recent government borrowing has been achieved through the issuance of nominal bonds, why was the reduction in borrowing achieved through the cessation of issuance of RRBs? Historically, changes in break-even inflation have provided a clue to RRB issuance levels.

Historical RRB auctions

Sources: Bank of Canada, Statistics Canada.

We see from the chart that when break-even inflation rates (blue) were approximately 2.5% in 2007, the government increased RRB issuance. As break-even inflation rates fell below 1.5% in 2019, the government chose to reduce issuance. This suggests the government has used a roughly 2% break-even inflation rate threshold to determine whether to increase or decrease RRB issuance. However, in recent months, break-even inflation rates rose steadily and were even above 2% when the decision to cease issuance was announced, suggesting that a static 2% threshold may not be considered sufficient by the government anymore it may be considering inflation risk at the time of issuance.

The previous graph includes a measure of annualized inflation in the five years prior to the issuance of an RRB (red). This measure has historically trended with break-even inflation rates. More recently, we have seen that break-even inflation rates have not risen at the same level of five-year annualized inflation. As a result, the Government of Canada may not feel appropriately compensated for the inflation risk taken by issuing RRBs compared to similar term nominal bonds. To sum it up, the demand may not exist at the price at which the government is willing to issue the RRBs.

In considering the impact of these break-even levels on the government’s financing costs, it’s worthwhile to remember that RRBs currently make up only 6% of amounts outstanding. We believe that it’s equally important for the Government of Canada to consider other factors when making decisions impacting the liquidity of the RRB market, such as the importance of the RRB market for pension plans with inflation-linked benefits.

Should liquidity decrease in the RRB market, investors can use other asset classes to hedge inflation risk. Examples of other investments that can replicate Canadian inflation include inflation-linked bonds of other countries (primarily U.S. Treasury inflation-protected securities [TIPS]) and inflation swaps. In addition, real estate and infrastructure show strong inflation hedging properties over longer time periods.