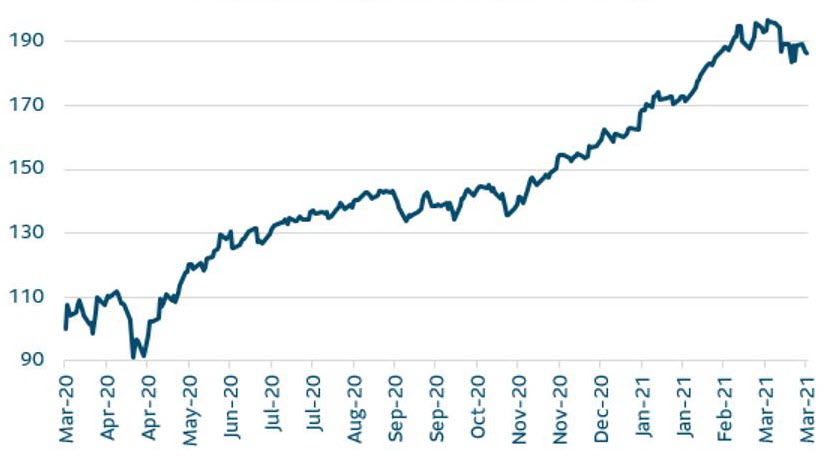

Commodity Index (SPGSCI)

Source: Bloomberg, SLC Management

While commodities tend to move together on growth surprises, they are not a monolithic crew. Metals, energy and agriculture are all part of the broad index but their individual dynamics can be nuanced and idiosyncratic.

Keeping commodity prices elevated for a long period usually involves some supply constraints, either natural or reluctance to make investments. For example, for capital intensive exploration, producers often hold back on bringing new resources online until they are confident that demand spikes are durable.

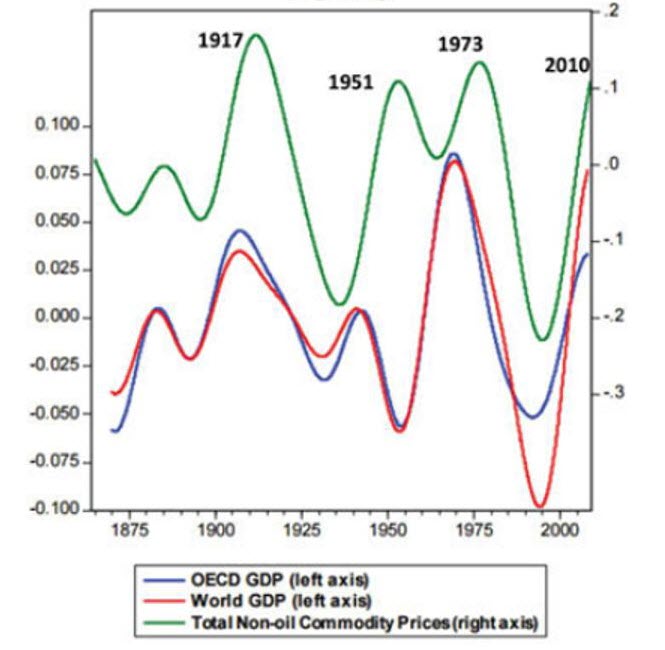

Supercycles Are Fairly Rare But Long Lasting

Since the mid nineteenth century there have been four supercycles, based on research from Bilge Erten and Jose Antonio Ocampo. They define a supercycle as a “decades long, above trend movements in a wide range of base material prices”. All four were underscored by major historical shifts.

The first significant commodities cycle began in the late 1890s as the US entered a rapid industrialization and urbanization phase. This accelerated as armament for the First World War erupted. While the cycle peaked in 1917, it continued until the early 1930s.

Super Cycle Components, Global Output and Total Non-oil Commodity Prices (Log scaling)

Source: Bilge, Erten, Jose Antonio Ocampo 2021 “Super-cycles of commodity prices since the mid-nineteenth century” DESA Working Paper

The next supercycle soon kicked in as Europe and eventually its allies, were engulfed in the Second World War. The resources and materials needed for the war effort were huge and the aftermath led to extensive reconstruction for both Europe and Japan. While the cycle peaked in 1951, it didn’t fade for another decade as post-war growth continued at a decent pace.

The early 1970s brought the third cycle. It was preceded by strong economic growth which led to a surge in prices for energy and materials which continued until the early 1980s. While demand was running high, supply was disrupted as countries nationalized extraction industries and foreign investors withdrew. Eventually producers started to shore up their supply and prices stabilized.

Finally, the most recent cycle started in 2000 as China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) and started to modernize its economy. Its rapid industrialization and the mass migration of workers to cities resulted in a building boom. Spending on infrastructure led China to become the top global consumer of most commodities. The cycle was interrupted by the 2008 financial crisis, but China’s response with a massive stimulus program restored demand. The cycle continued to 2014 when oil oversupply finally kicked in.

Now, as world economies emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, investors are trying to make sense of early supercycle indicators like price increases. Part of the current price surge has been driven by interruptions in supply as workers get waylaid by the pandemic. Weather has also played a role: stints of drought in South America for instance affected agricultural output as grain production dropped. Additionally, as economies reopen, activity keeps improving and at some point that will stabilize.

While all of this is positive, it is not enough to keep prices elevated for decades. Usually it takes a structural shift to drive a supercycle. However, there is one asset that may fit the bill, and that’s copper. As major economies embrace sustainability and the switch from fossil fuel to electric solutions gains momentum, copper will be central to that green revolution.

Copper’s Expanding Role

Copper’s key role in construction and major appliances is longstanding. But it is also central to supporting the shift to climate-friendly solutions. It is essential for batteries, electric cars, solar panels, wind turbines and 5G solutions. It is also the lifeline for connecting renewable energy to the grid.

Glencore Plc, the international trading and mining company, estimates that the global demand for copper could double in the next thirty years. It also cautions that the capital investment in developing new mines is significantly below what’s needed.

This vulnerability has also been underscored by S&P Global Market Intelligence. Their research shows that over the last 30 years, 224 sizeable copper deposits have been discovered. However, only 16 of those have come in the last decade and only one since 2015. Of those 224 deposits, 144 are still in assessment or development while the other 80 are either in production or have closed. This conversion ratio from exploration to production is poor.

While it takes 7 to 10 years to develop a mine, most of the delays in bringing mines online has been due to cost cutting. Over the last few decades copper producers have trimmed their exploration budgets. In turn, they have focused more on increasing the efficiency of existing mines. While this has made mining cash flows more dependable, the industry now lacks some flexibility to quickly ramp up production.

Sustainability Efforts Could Drive A Supercycle

This broad dynamic of increasing copper demand coupled with relatively inflexible supply will likely prevail for several years. Global commitments to green infrastructure, transition to electric vehicles and ESG aware investors seem like long term demand drivers. Meanwhile, suppliers have been cautious on exploration spending.

Higher prices will eventually bring more supply online, but given the long mine development cycle, that will take time and keep prices elevated. Therefore, copper should be well positioned for an extended bull run over the next decade. A lot certainly depends on how quickly the renewable energy buildout happens. But governments and societies seem convinced that sustainability efforts cannot be delayed. With this in mind, investors should remain optimistic of commodities more broadly, but wary of any premature declarations of an overall commodities supercycle.

This article first appeared in Forbes. This material contains opinions of the author, but not necessarily those of Sun Life or its subsidiaries and/or affiliates.